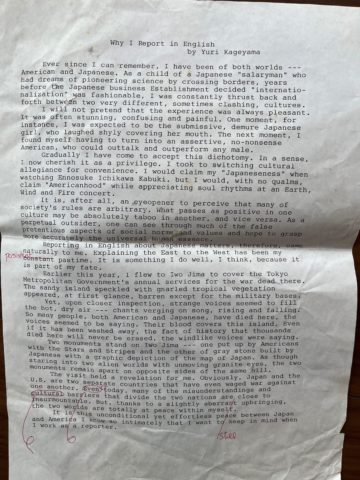

Why I Report in English by Yuri Kageyama

This is something I just happened to find in my desk, typed up (yes, typed _ remember those days?). It’s an essay about why I am a reporter, and why I report in the English language that I wrote I think in the 1980s. Perhaps I was applying for work? It is long before I joined The AP. I am not changing the wording, but have put it down exactly the way it is typed on the sheet of paper, except for the four changes made in red in pen that were already there. I might write it differently today. But I feel exactly the same. So here goes:

Ever since I can remember, I have been of both worlds _ American and Japanese. As a child of a Japanese “salaryman” who had dreams of pioneering science by crossing borders, years before the Japanese business Establishment decided “internationalization” was fashionable, I was constantly thrust back and forth between two very different, sometimes clashing, cultures.

I will not pretend that the experience was always pleasant. It was often stunning, confusing and painful. One moment, for instance, I was expected to be the submissive, demure Japanese girl, who laughed shyly covering her mouth. The next moment, I found myself having to turn into an assertive, no-nonsense American, who could outtalk and outperform any male.

Gradually I have come to accept this dichotomy. In a sense, I now cherish it as a privilege. I took to switching cultural allegiance for convenience. I would claim my “Japaneseness” when watching Ennosuke Ichikawa Kabuki, but I would, with no qualms, claim “Americanhood” while appreciating soul rhythms at an Earth, Wind and Fire concert.

It is, after all, an eyeopener to perceive that many of society’s rules are arbitrary. What passes as positive in one culture may be absolutely taboo in another, and vice versa. As a perpetual outsider, one can see through much of the false pretentious aspects of social norms and values and hope to grasp more accurately the universal human essence.

Reporting in English about Japanese matters, therefore, came naturally to me. Explaining the East to the West has been my persistent pastime. It is something I do well, I think, because it is part of my fate.

Earlier this year, I flew to Iwo Jima to cover the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s annual services for the war dead there. The sandy island speckled with gnarled tropical vegetation appeared, at first glance, barren except for the military bases.

Yet, upon closer inspection, strange voices seemed to fill the hot, dry air _ chants verging on song, rising and falling. So many people, both American and Japanese, have died here, the voices seemed to be saying. Their blood covers this island. Even if it has been washed away, the fact of history that thousands died here will never be erased, the windlike voices were saying.

Two monuments stand on Iwo Jima _ the one put up by Americans with the Stars and Stripes and the other of gray stone built by Japanese with a graphic depiction of the map of Japan. As though staring into two alien worlds with unmoving granite eyes, the two monuments remain apart on opposite sides of the same hill.

The visit held a revelation for me. Obviously, Japan and the U.S. are two separate countries that have even waged war against one another. Today, many of the misunderstanding and barriers that divide the two nations are still close to insurmountable. But thanks to a slightly aberrant upbringing, the two worlds are totally at peace within myself.

It is this unconditional yet effortless peace between Japan and America I know so intimately that I want to keep in mind when I work as a reporter.