AN UNDENIABLE FACT

A haiku by Yuri Kageyama

March 8, 2020 8:55 a.m.

Some

Writing

has no

Soul

No Voice (No Story being told)

It

Comes

from

Within

Artwork by Munenori Tamagawa

SOME PEOPLE a poem by Yuri Kageyama

Some people are Poison

In sheer Presence

Even from afar

Some people are Garbage

A stench of Gibberish

Even from afar

Some people are Ineffectual

A blob hanger-on

Even from afar

Some people are Broken

A Godzillion pieces

Never whole again

Some people are Forgotten

Hidden unbleedingly silent

Into the flesh of scars

Some people are Music

Wafting healing savory sweet

Even from afar

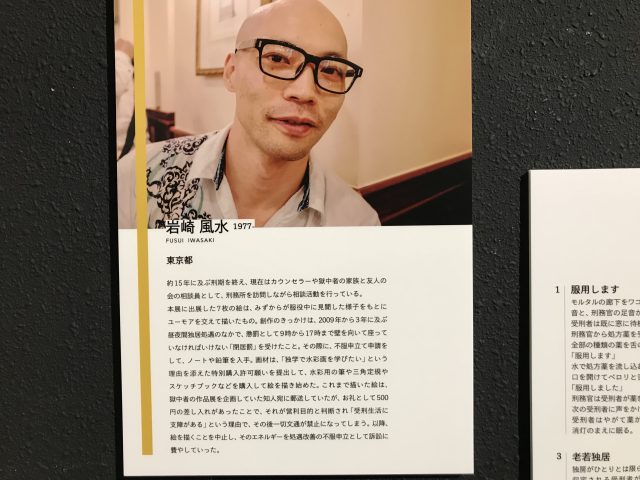

I met the former inmate behind this story a few years ago, in 2016, when I was putting together my story “The Very Special Day” with artwork by Munenori Tamagawa. I was thinking of just stapling together printouts, but the visual artist had other ideas. He wanted a real book, and he said he knew someone who knew how to design books, a skill, as it turned out, he had learned in a Japanese prison. I didn’t ask questions. I just assumed he had committed a serious crime because of the long time he had been incarcerated, but felt he deserved to be treated no different from anyone else as he had served his time. I did not even know until he told me his story that he was asserting his innocence. This is his story:

He spent 15 years behind bars for a murder he confessed to, but he says he didn’t commit. His father hanged himself in shame. While in prison, he bit off a piece of his arm in a suicide attempt. Placed on half a dozen tranquilizer pills, he was an addict by the time he finally got out, four years ago.

Fengshui Iwazaki, who has changed his name to protect himself from the social backlash, is still trying to adjust to being back in the real world.

“Fifteen years _ that’s a whole generation in a lifetime,” he says, his eyes clear, child-like, much younger than his 41 years.

His story underlines the treatment convicts get in Japan, a society that’s so insular and crime-free most people don’t know much about what it’s like to live the life of a criminal. The arrest of Nissan’s former Chairman Carlos Ghosn, charged with financial misconduct, is helping bring international scrutiny to this legal system, which human rights groups have long criticized as harsh and unfair.

Iwazaki had never before spoken to me about his experiences, how two decades ago, he had made headlines as a murderer.

“It was as though I was a monster,” Iwazaki recalled.

^____<

Iwazaki and others who went through Japan’s criminal system say prosecutors and police come up with a story-line for a confession. While interrogated, Iwazaki was taken to the mountains where the body had been found and directed to point in the right spots, he said.

His girlfriend had been strangled to death, and he instantly emerged the prime suspect.

He resisted at first but signed the confession after three weeks of being interrogated daily without a lawyer present, standard practice in Japan.

He says he was bullied, his hair pulled, the table banged. After a while, it was easy to cave in.

He believes the real murderer might be the man who had adopted his then-3-year-old daughter from a previous relationship. He had planned to live near her someday, not ever telling her he was the father, just to be close to her. She died in a car accident while he was serving time.

Prosecutors say they are merely doing their jobs and didn’t create the system.

Defense lawyers say suspects sign false confessions and don’t realize it’s too late to assert innocence later in a trial.

That’s why it is called “hostage justice.”

Judges tend to believe the prosecutors’ story line: the conviction rate in Japan is higher than 99%.

Going against such a powerful trend takes tremendous courage. Unlike the U.S., prosecutors can appeal, meaning innocent verdicts can get overturned in a higher court.

^___<

The life of imprisonment Iwazaki describes is austere, isolated and regulated. Each prisoner gets a tiny cell with a toilet and bedding, unless the prison gets crowded and cells get shared, a condition that’s increasingly rare.

Communication among inmates is limited to the 30 minutes of outdoor exercise, or the evening hours, during which TV is allowed.

Whenever inmates are transported, they wait in enclosed booths lined next to each other so prisoners won’t mingle, called “bikkuri-bako,” or “jack-in-the-box.”

Every morning, the convict changes into green prison garb and gets marched to a factory within the prison grounds.

Iwazaki did menial work like placing wooden chopsticks into paper wrapping and packing them in boxes. He also learned how to work the printing presses.

The toughest time was his three-year solitary confinement doled out as punishment for being a troublemaker, he said.

One time, out of frustration, he smashed a window with his bare hand, which added half a year to his sentence.

He was always curious about why others were locked up.

One inmate, he learned, had tried to steal money from an ATM to send his son to college. When a guard found him, he used a stun gun. The guard had a weak heart and died. And so the charge became murder while committing grand larceny, a serious offense.

“There are no really bad people in prison,” Iwazaki says with a conviction that is startling.

^____<

There is little in Japanese society that helps people adjust to life after incarceration.

When Iwazaki was released, he only had 1,000 yen ($9). He checked into a hospital, pleading insanity. He was running out of the pills prescribed at the prison.

He finally made it to Eizo Yamagiwa, a filmmaker who has devoted his life to supporting prisoners. Yamagiwa, who had visited Iwazaki in prison, gave him money, and Iwazaki finally made it home to his mom.

Yamagiwa says only the authorities’ side of the story gets relayed in Japan, influencing judges and juries so that trials tend to merely work as rubber-stamps for the prosecutors.

The prison system, he said, is so devastating most people come out sick and unable to continue with their lives.

He said Iwazaki was an exception in working hard to live a normal life.

^___<

Iwazaki, who had originally planned to become a schoolteacher, has had his life forever changed.

Retrials to try to overturn guilty verdicts are rarely granted in Japan. Usually, totally new evidence such as a DNA test is needed.

Iwazaki is hesitant even to try. His case is tough because of the mounds of evidence submitted during his trial, including his confession. His mother has asked he doesn’t pursue a retrial; she doesn’t want to think about any of it ever again.

Iwazaki lives alone in a stark room with a tiny drab kitchen and a bathroom. A desk and two chairs are the only furniture.

On the walls are two drawings signed Masahiro, a man who died on death row. Done meticulously and entirely by pen and pencils, one depicts a bouquet of red roses, the other, Mary and baby Jesus. No one except for Iwazaki had claimed them.

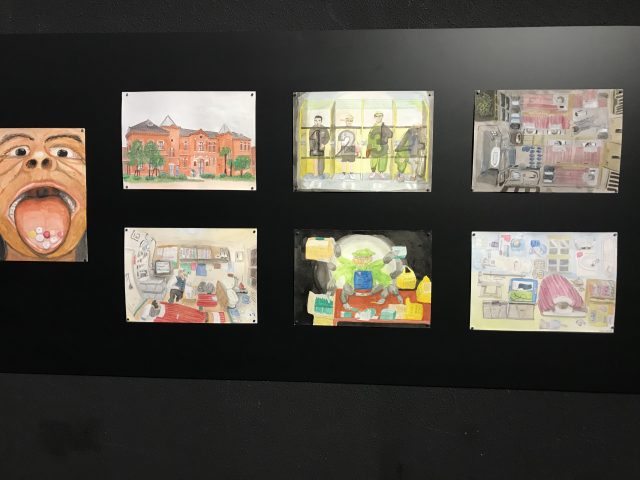

Iwazaki also drew pictures while in prison: A big close-up of his open mouth filled with pills, a bird’s eye view of his cell, an inmate working so hard in the factory he is turning into a blur.

The drawings were part of a show of “art by outsiders” in April 2019, in Tokyo, a milestone for Iwazaki. While in prison, authorities had forbidden such exhibits.

Iwazaki is also in a training program to counsel addicts. He already works as a counselor, having studied various therapy methods, which he says helps calm him. Completing the training means better pay.

He has also found a girlfriend, a carefree woman who works at a dot.com and is passionate about saving lions in Africa. They plan to get married and maybe have children.

GRAVES FOR THE LIVING _ a poem by Yuri Kageyama

Graves aren’t for

Those Buried only

They’re for those

Who’re still Alive _

They don’t Speak Back,

They don’t expect Much,

Ready to be Forgotten

If not already Forgotten;

So Go There,

To the Graves,

While You Live,

To Be Forgiven:

Graves Are

Gifts From the Dead

For the Living.

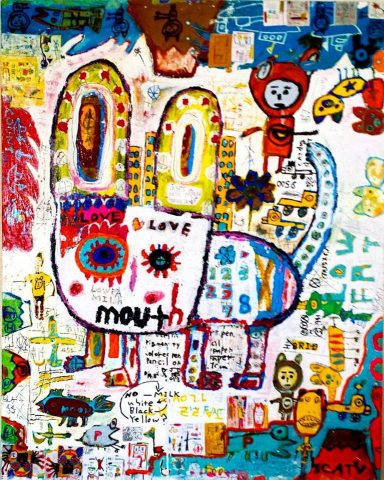

Artwork by Munenori Tamagawa

A COLLABORATION OF VISUAL ART, THE SPOKEN WORD AND MUSIC

THE VERY SPECIAL DAY

What: I read my poetry/story “The Very Special Day” while Munenori Tamagawa paints to guitar by Yuuichiro Ishii.

Where: Nagai Garou’s Tachikawa Gallery 1-25-24 Nishi Building 4 Fl Fujimicho Tachikawa, Tokyo TEL: 080‐9573‐5655

When: SAT Oct. 28, 2017 from 3 p.m. Reception party follows from 4:30 p.m ~ 6 p.m.

Who: Munenori Tamagawa, “the Basquiat of Japan,” has shown his work at the Seattle Art Fair, Tachikawa Art Brut and the streets of Tokyo, including Innokashira Park and the Shiodome Art Market.

Guitarist Yuuichiro Ishii, who studied recently at the Berklee College of Music on a prestigious scholarship, has performed with Fuyu, Mika Nakashima and Yusa, as well as my Yuricane spoken-word band.

Why: To celebrate the exhibition of Munenori Tamagawa’s recent works.

More What: Last year, Munenori Tamagawa and I created the children’s book THE VERY SPECIAL DAY, which brings together my story with his illustrations. More information on our evolving collaboration.

Artists make any day a very special day when we come together.

Video by Naomi Yoshida

Photo by Seiko

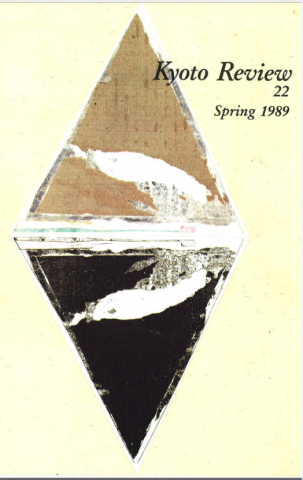

Kyoto Review cover

The writer Yo Nakayama has also translated my poems.

I so liked his versions I’ve read them with my poems.

Mr. Nakayama is an academic and a poet, too, and he has a flock of long hair and reading glasses maybe, and he is wise and soft and brave.

Or so I imagine, as although I maybe have met him, I can’t really remember.

I vaguely remember reading this review when I was younger, and frankly I didn’t really think much of it.

I was too busy dealing with things that went with trying to survive and being creative I did not really appreciate how this older poet was being supportive and so poignant.

And so poetic.

I am older now and do.

Nakayama died in 1997, it says online.

But his writing lives on.

Here, this person I know through Facebook, of all ways, has shared in a message this precious, kindhearted review of my work.

I am grateful, of course, and feel blessed.

But I also feel a sense of vindication about being a poet _ that we are all connected in doing the right, eternal thing by being poets.

Please read the review.

I’ve also updated my Review section on my site with this addition,

Sorry this is belated but thank you, Mr. Nakayama, truly from the poet’s heart:

Saying it her own way

a book review by Yo Nakayama in Kyoto Review, 22, Spring 1989

of “Peeling” by Yuri Kageyama, I. Reed Books, Berkeley, CA

New and important. Yuri Kageyama was born in Japan, but grew up in American culture.

Her work as contrasted with those of previous generations is very articulate and beautiful.

Should you take up this, her collection of poetry, you’ll find 32 exciting poems under five different sections.

In the first section she remembers time spent with her mother. Yuri seems to know where she is from, as here in a poem in which she describes her mother’s profile.

Her face from the side

the cheekbones distinct

is an Egyptian profile sculpture

an erotic Utamaro ukiyoe

and her mother’s lessons:

As soon as I would awake some chilly morning, she would

tell me to go smell the daphne bushes leading to our door.

I still remember their fresh fruitlike pungence

As Yuri grows older, she becomes uncomfortable with her mother and begins to hate her and her culture, which is alien to the American scene.

I dread your touch

when you return

that melts the hurt and vengeance

of wishing

to strangle you

Yuri feels almost physically hurt when she thinks of it. This is one of the characteristics your easily notice in her poetry. She is a physical writer, by which I mean that Yuri tries to write out of her own physical senses, especially when she talks about her involvement with music. In a short poem, “Music Makes Love to Me,” she confesses, “Music makes love to me everyday/ spilling cooled cucumber seeds/ wet flat disks to the tongue/ tickling/ shooting them with exalta-jaculation into my ear//” or in the section “Thought Speak,” she conveys her inner sensations as she listens to music:

music

is

the frantic flap of love doves taking dawn pre-cognizing flight

outside our window

music

is

the silence

between/your kisses

Or she describes her inner world as follows:

eyes closed

forsaken bamboo forest of the mind

hands groping

burrowing darkness like the earth

reaching out

shaking blood

muted and alone

As a young Japanese woman living in America, Yuri is constantly exposed to the situation that she has to say what she has to say: she, however, says it her own way, and I like it very much.

“A Categorical Analysis of the Asian Male or the Guide to Safe and Sane Living for the Asian Female” is a very funny piece in which she says there are four types: the Street Dude or “Lumberjack,” the Straight Dude or “Stereotype,” the Out There Dude or “Bum,” and finally the type four she calls the Ideal Dude, but this is the “Obake,” or the ghost, that is, she says “the perfect man who does not exist.” Once, Filipino writer Carlos Bulosan wrote that in America being a Filipino is a crime. And Yuri is, she says, “tired of the laundry men/ and the dirty restaurant cooks (cuz) they don’t have the powers.”

it’s okay

you see only the race in me

….

It’s okay

cuz, white man,

you have

whiteness

to give

The best part of the book is, however, that which deals with her physical intimacy with her lovers and her own baby. She could have written a categorical analysis of a male partner or the guide to safe and safe mating for a serious woman as well. Only after she has a baby of her own, she begins to realize the importance of the “Strings/Himo,” which she once wanted so badly to break out and couldn’t. Her reflection on the total life: “Having Babies Versus Having Sex” is the final poem in this book. When she sees her man rocking the baby, and looks into Isaku’s eyes and cries with him, she reaches her conclusion: this is the culmination of her womanhood.

Your eyes

Are my eyes

That see and see what I have seen

They can’t ever understand

The love of a Japanese woman

Who waits

Pale powdered hands

Eyes downcast night pools of wetness

Fifteen years for her samurai lover

And when he comes back

Nothing’s changed

Nothing’s changed

These poems could never have been written by anyone but a poetess who has gone through the labor Mother Nature imposes upon the one who creates. If not for Yuri’s sensitivity and capability, this book wouldn’t have been born.

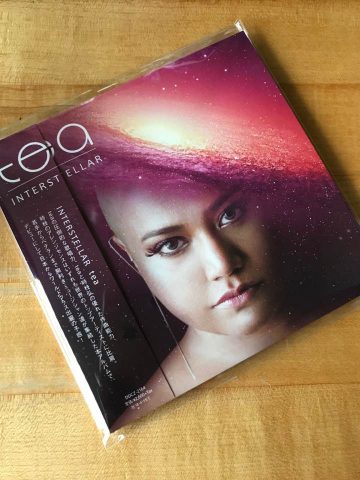

Two of my songs in this new album

“Oh My Buddha” and “I Will Bleed,” two songs I co-wrote with Hiroshi Tokieda and Tea, are part of this great album that just came out (October 2017).

“Oh My Buddha” (audio of an earlier reading in the link) is an Asian take on what we often say: “Oh My God,” something that Toshinori Kondo pointed out some time back as what we should be saying as Asians.

And so I imagined what it would have been like to have been married to a great man like Buddha.

It might have not been as wonderful as it might seem.

Tea and I were talking about how fun it would be to write a pop song that was inspired by an Indian theme.

And so this is what we did.

I even rap or read my poem in the recording _ woooh la la !!

OH MY BUDDHA

_ a song about faith, love and other things

By Yuri Kageyama

REPEATING THEME:

My name is Yasodhara

Wife of Buddha

Mother of Rahula

I ride a white elephant

I am Siddharta’s woman

VERSE 1

You took off to find Nirvana

Became a hero for the poor

You just took off one sunny day

And found enlightenment

While I’m stuck in the kitchen

Barefoot and pregnant, alone

(Repeat theme)

VERSE 2

You’ve started a religion

See statues in your likeness

Of gold and bronze and wood

Sitting prim on that lotus

While I’m having your babies

Feeding them, aborting them, alone

(Repeat theme)

VERSE 3

You remember I cooked you breakfast?

So you could go and contemplate

Sitting 49 days under the Bodhi tree

To discover, sacrifice, meditate?

While I’m crying in my misery

Breathing my prayers, alone

(Repeat theme)

REFRAIN

You’re a superstar

I’m a nobody

You live in history

I die unknown

When I awoke

There was no sign of you

When I awoke

There was no sign of you

My universe went up in smoke

My universe went up in smoke

Oh, my Buddha

Oh, my Buddha

I am planning a music video, and I have asked Toshinori “Toshichael” Tani to come up with choreography.

He will dance in the video, which I will film.

“I Will Bleed,” to me, evokes a lot of things _ abortion, miscarriage, birth, heartbeat, love, death.

Love is such a powerful force it is both horrible and awful.

My poem is about that horror, inspired by the double suicides of Chikamatsu, which highlight how the puppets, in death, are able to transcend how miserable, human and lowly they were before that moment of death.

That beauty to me is about the kind of love that crosses boundaries, overcoming racism and other small, discriminatory, confining preconceptions.

It speaks of the potential of our human condition.

I wrote the poem for Hiroshi and Tea.

But it is a poem for all lovers, and the hope love will overcome hate around the world, through the purification of our bleeding.

OLD WOUNDS

_ a poem by Yuri Kageyama

the pain throbs

gnarled stuck intestines

wobbly knobs of scars inside

tracing where the knife slashed

to deliver your son

so many years ago

the bleeding has healed

betrayal, forgiven but not forgotten,

sealed lips of hushed kisses,

the chasm of hurt

tugging, tearing at your chest,

has turned into heartbeats

fading with age

just going

da-thump da-thump da-thump

barely murmurs

whispers of skin

you were young then

and had dreams,

not knowing other things,

unlike honor,

can elude,

again, and again,

for skin color, sex, age,

growing used to anonymity

outgrowing disappointment

but old wounds

they hurt like new wounds

DECONTAMINATION GHOSTS a performance poem by Yuri Kageyama an excerpt from “NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA: Meditation on an Under-Reported Catastrophe by a Poet” being performed at Z Space in San Francisco July 8-9, 2017. Written by Yuri Kageyama. Directed by Carla Blank. Performed by Takemi Kitamura, Monisha Shiva and Shigeko Sara Suga with Music by Melvin Gibbs, Isaku Kageyama and Kouzan Kikuchi. Lighting by Blu. Film by Yoshiaki Tago.

(with video and Drum and Fue, as in Kabuki Ghost scenes)

(In English speak normally, quickly)

Flexible Container

(Chant very slowly in Japanese, both voices together)

Fooh reh kooh she boo rew

Kon tay nah

Fooh reh kooh she boo rew

Kon tay nah

Fooh reh kooh she boo rew

Kon tay nah

Flexible Container

Foo reh kon

Foo reh kon

Foo reh kon

(One voice starts counting slowly and keeps counting slowly in Japanese. Overlay as the other voice starts, with the slow mechanical Japanese chant)

Hitotsu Futatsu Mittsu Yottsu Itsutsu Muttsu Nanatsu ….

Foo reh kon

Foo reh kon

Foo reh kon

Fooh reh kooh she boo rew

Fooh reh kooh she boo rew

Fooh reh kooh she boo rew

Kon tay nah

Kon tay nah

Kon tay nah

(fade out)

Note to readers: The Japanese government is backing expensive projects for giant shovels to scrape off topsoil in a stretch of land as big as the state of Massachusetts, and storing them in plastic bags, mounds and mounds of them _ 13 million flexible containers by the official count _ so areas in Fukushima can be declared safe enough for people to come back and live. This wasn’t attempted in Chernobyl, or any place in the world. The government is ending aid in March for those who evacuated from the areas being declared safe after decontamination. Before the 2011 nuclear accident, the government used to set the safe limit for radiation exposure at about 1 millisievert a year. But these days health experts are saying the definitive link with cancer is detected scientifically at 100 millisieverts a year or higher, and so Fukushima people at most will be exposed to far less at under 20 millisieverts, which, they say, would be safe.