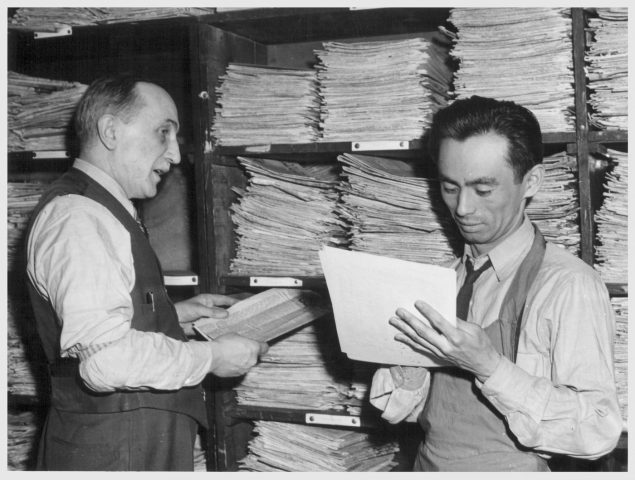

Joe Oyama in an Online California Archives photo, as he stands in the New York headquarters of the Common Council for American Unity. Joe was assistant editor of the Japanese American daily in Los Angeles before he was interned, in Santa Anita Assembly Center and Jerome Relocation Center, where both he and his wife Sami worked as journalists. After moving to New York in 1944, he was editor of the News Letter of the Japanese American Committee for Democracy. He and his wife were also both actors. They moved to Berkeley in their later years. I got to know him and Sami and their two children, who are also great artists. Joe was always supportive of my poetry: “Like champagne,” he said once. This poem is for Joe and all the other great journalists. May the legacy live on.

A Poem for Journalism

By Yuri Kageyama

A Tree, a Story, a Drum

Circles carved times over,

Coded rhythms of continents

Animal skin stretched, carefully nailed,

So our heartbeat is not lost _

The snare, congas, kpanlogo, tabla, taiko,

Talking drums speaking faraway tongues _

Stories killed, stories buried,

Stories denied, stories untold,

Perhaps we were just not stopped before

When our stories were not dangerous

But the Reporter is still here.

Hear the words

And see what they have seen:

Robert and Dori Maynard

Woodward and Bernstein

Margaret Bourke-White

Howard Imazeki

Gary Webb

Robert Capa

Anja Niedringhaus

Gerald Vizenor

Gwen Ifill

Joe Oyama

Gordon Parks

Hear that Music in the Skin,

Feel that Story in the Tree,

Banned by slave owners,

The Drum holds the Message,

The Pow Wow stirs in starlit nights

The Slap-Tone conviction that comes to us

The Dance cannot be silenced; listen:

Printers rumble, digital pages scroll, newspapers turn,

Borders fade into illusory walls,

Starving children, covered up documents, the ravages of war

The Voice through the centuries

Asking Questions

Even if no one cares to hear the Answers,

Accurate, objective, fast, ethical

No matter what they say,

I am deranged but I am not deranged

I am fake but I am not fake

I am afraid but I am not afraid

I am the Drum, the Tree, the Story.