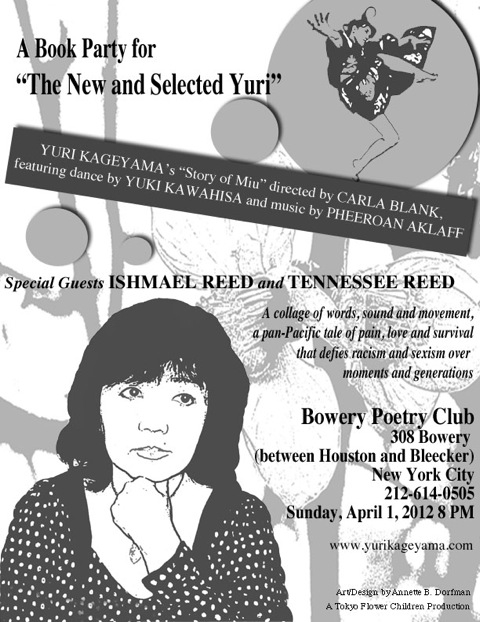

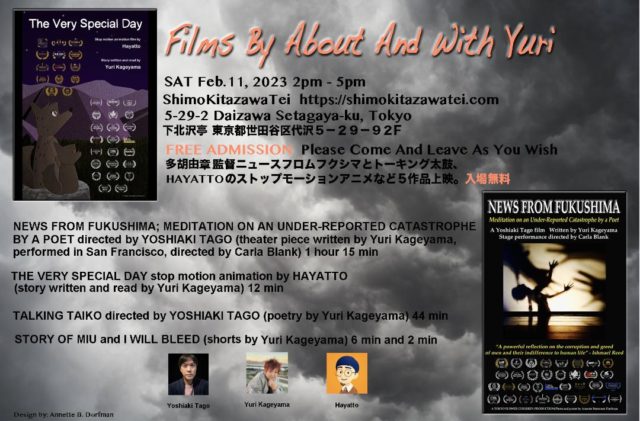

FILMS BY ABOUT AND WITH YURI SAT Feb. 11, 2023 in Tokyo

Five films, all featuring bilingual/bicultural poet/storyteller YURI KAGEYAMA, were shown at a tiny Tokyo club. Among the works are two directed by YOSHIAKI TAGO: A performance by American-based actors and musicians in San Francisco, and a documentation of Kageyama’s reading in Japan. Stop motion artist HAYATTO has painstakingly created animation of Kageyama’s short story. SAT Feb. 11, 2023, from 2 p.m. ShimoKitazawaTei https://shimokitazawatei.com/ FREE ADMISSION

詩人カゲヤマユウリが関わった5作品が東京で上映された。映画、テレビドラマなど数多くてがける多胡由章監督のニュースフロムフクシマとトーキング太鼓の他、国内海外活躍のストップモーションアーティストHAYATTO のアニメなどが下北沢亭 https://shimokitazawatei.com/

2月11日(土) 午後2時 入場無料。

ARTIST BIOS プロフィ―ル

YOSHIAKI TAGO directed “Sabai Sabai,” “Women at the Cash Register,” “Worst Contact,” as well as many Japanese TV drama shows, including “Atomu No Ko.” He won an award at the Yasujiro Ozu Memorial Film Festival. A graduate of the prestigious Japan Institute of the Moving Image, founded by Shohei Imamura, Tago has worked with Nobuhiko Obayashi, Takashi Miike, Takashi Murakami and Macoto Tezuka.

多胡由章監督は映画「サバイサバイ」「夜の底で魚になる」「レジを打つ女」「ワーストコンタクト」 他、「アトムの童」などテレビ番組も数多く手掛ける。小津安二郎記念蓼科高原映画祭受賞。日本映画大学卒。大林宣彦、三池崇史、村上隆、手塚眞とコラボ。

HAYATTO specializes in stop motion film, in which the figures he makes by hand are moved, with a minimum of eight frames needed per second. His credits include “Box Cats,” as well as advertising for T-fal and Mitsui Sumitomo.

HAYATTO が特化するストップモーションは手造りのフィギャーやパーツをすこしづつ動かし少なくとも一秒8フレームで表現する「愛あふれる」作品。ショート「ハコネコ」やT-falや三井住友の広告で活躍。

YURI KAGEYAMA is a poet, writer, journalist and filmmaker born in Japan and raised in Maryland and Alabama. Her books include THE NEW AND SELECTED YURI (Ishmael Reed Publishing Co.). Her works are in KONCH, Bigotry on Broadway (Baraka Books), Life and Legends, Tokyo Poetry Journal and many other literary anthologies and magazines.

カゲヤマユウリ(影山優理)は日本生まれアメリカ育ちの詩人、ものかき、ジャーナリスト、ビデオ作家。

著書にはTHE NEW AND SELECTED YURI (Ishmael Reed Publishing Co.) など数多くの文芸雑誌や文集に掲載。

^______________________<

FREE ADMISSION Free Drink And Come/Leave As You Wish.

入場無料 出入り自由 無料ドリンク付き

下北沢亭 https://shimokitazawatei.com/

東京都世田谷区代沢5−29−9 2F

5-29-2 Daizawa Setagawa-ku Tokyo

SAT Feb. 11, 2023 2 p.m. ~ 5 p.m.

2023年2月11日(土)午後2時 ~ 5時

上映順と時間 Works in order of screening and duration:

I WILL BLEED, STORY OF MIU by Yuri Kageyama 2 min, 6 min

THE VERY SPECIAL DAY by HAYATTO 12 min

NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA by Yoshiaki Tago 1 hour 15 min

Q&A with the artists 作者達との談話 20 min

TALKING TAIKO by Yoshiaki Tago 44 min