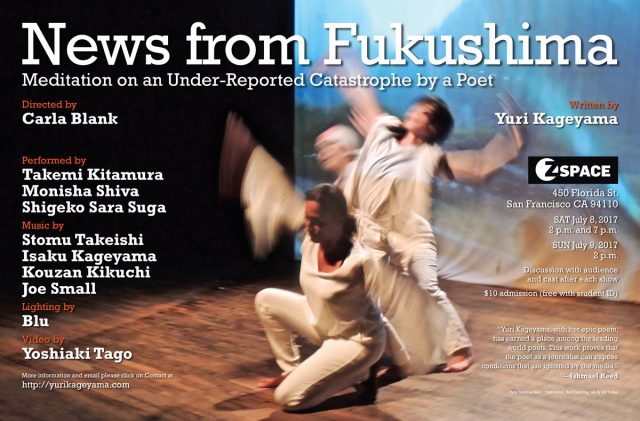

NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA: Meditation on an Under-Reported Catastrophe by a Poet

NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA

Meditation on an Under-Reported Catastrophe by a Poet

Written by Yuri Kageyama | Directed by Carla Blank

Z Space 450 Florida St. San Francisco CA 94110

SAT July 8, 2017 2 p.m. and 7 p.m.

SUN July 9, 2017 2 p.m.

$10 admission (free with student ID)

Discussion with audience and cast after each show.

For tickets and other information, please click on this special Z space site.

“Yuri Kageyama, with her epic poem, has earned a place among the leading world poets. This work proves that the poet as a journalist can expose conditions that are ignored by the media.” _ Ishmael Reed

“A commentary on what it means to be human in the 21st Century.” _ Basir Mchawi

“A beacon of light in a darkening world.” _ Paul Armstrong

“Tough yet faithful production and its dedication to truth-telling.” _ David Henderson

“The nuclear age of post-World War II Japan has never ended.” _ Hisami Kuroiwa

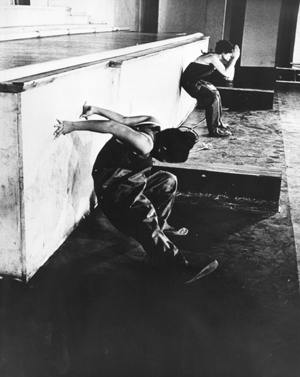

The performers in NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA: From left to right: Shigeko Sara Suga, Monisha Shiva, Takemi Kitamura (photo by Tennessee Reed)

Fukushima is the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl. It will take decades and billions of dollars to keep the multiple meltdowns under control. Spewed radiation has reached as far as the American West Coast. Some 100,000 people were displaced from the no-go zone. But, six years after 3.11, the story hardly makes headlines.

Journalist Yuri Kageyama turns to poetry, dance, theater, music and film, to remind us that the human stories must not be forgotten. Carla Blank, who has directed plays in Xiangtan and Ramallah, as well as collaborated with Suzushi Hanayagi and Robert Wilson, brings together a multicultural cast of artists to create provocative theater. Performing as collaborators are actors/dancers Takemi Kitamura, Monisha Shiva, Shigeko Sara Suga and musicians Stomu Takeishi, Isaku Kageyama, Kouzan Kikuchi and Joe Small. Lighting design by Blu. Documentary video of Fukushima by Yoshiaki Tago.

NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA is a literary prayer for Japan. It explores the friendship between women, juxtaposing the intimately personal with the catastrophic. The piece, which had a debut run at La MaMa in New York in 2015, continues to develop and premieres on the West Coast at Z Space in San Francisco.

For more information, interviews and other queries:

Please click on Contact

BIOS OF THE ARTISTS: Yuri Kageyama. Photo by Junji Kurokawa.

THE PLAYWRIGHT

YURI KAGEYAMA is an award-winning journalist, poet, songwriter, filmmaker and author of “The New and Selected Yuri” and “The Very Special Day.” Her spoken-word band the Yuricane has featured Melvin Gibbs, Eric Kamau Gravatt, Morgan Fisher, Pheeroan akLaff and Winchester Nii Tete. She is published in ”Breaking Silence,” “On a Bed of Rice,” “Pow Wow,” Cultural Weekly, Y’Bird, Konch and Public Poetry Series. http://yurikageyama.com/

THE DIRECTOR Carla Blank

CARLA BLANK is a writer, editor, director, dramaturge and a teacher and performer of dance and theater for more than 50 years. She worked with Robert Wilson to create “KOOL _Dancing in My Mind,” inspired by Japanese choreographer Suzushi Hanayagi. She directed Wajahat Ali’s “The Domestic Crusaders” from a restaurant reading in Newark, California, to Off Broadway and the Kennedy Center. http://www.carlablank.com/bio.htm

THE ACTORS

TAKEMI KITAMURA, choreographer, dancer, puppeteer, Japanese sword fighter and actor, appeared in “The Oldest Boy” at Lincoln Center, “The Indian Queen” directed by Peter Sellars; “Shank’s Mare” by Tom Lee and Koryu Nishikawa V; “Demolishing Everything with Amazing Speed” by Dan Hurlin and “Memory Rings” by Phantom Limb Co. She has worked with Nami Yamamoto, Sondra Loring and Sally Silvers. http://takemikitamura.com/

TAKEMI KITAMURA (CENTER). PHOTO BY TENNESSEE REED.

MONISHA SHIVA. PHOTO BY TENNESSEE REED.

MONISHA SHIVA is an actor, dancer, choreographer and painter, appearing in “The Domestic Crusaders” and “The Rats,” for theater, and independent films such as “Small Delights,” “Carroll Park,” “Echoes” and “Ukkiya Jeevan.” A native New Yorker, she has studied classical Indian dance and Bollywood, jazz and samba dancing, and acting at William Esper Studios and Studio 5. http://www.monishashiva.com/Monisha/home.html

SHIGEKO SUGA (LEFT). PHOTO BY TENNESSEE REED.

SHIGEKO SARA SUGA, actress, director, artistic associate at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, and Flamenco and Butoh dancer, has performed in 150 productions, including Pan Asian Rep.’s “Shogun Macbeth” and “No No Boy.” She dedicates her performance to her nephew Ryoei Suga, who volunteered in Kesennuma after the 2011 tsunami and now devotes his life there as a fisherman and monk. www.shigekosuga.com

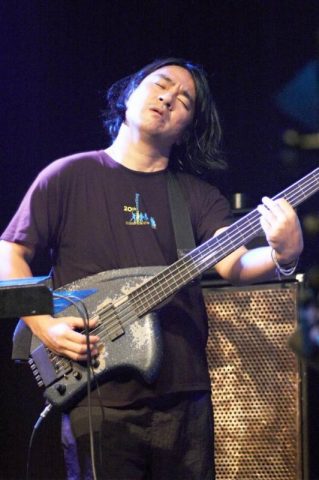

THE MUSICIANS

STOMU TAKEISHI is a master of the fretless electric bass and has played and recorded in a variety of jazz settings with artists such as Henry Threadgill, Brandon Ross, Myra Melford, Don Cherry, Randy Brecker, Satoko Fujii, Dave Liebman, Cuong Vu, Paul Motian and Pat Metheny. He tours worldwide and performs at various international jazz festivals.

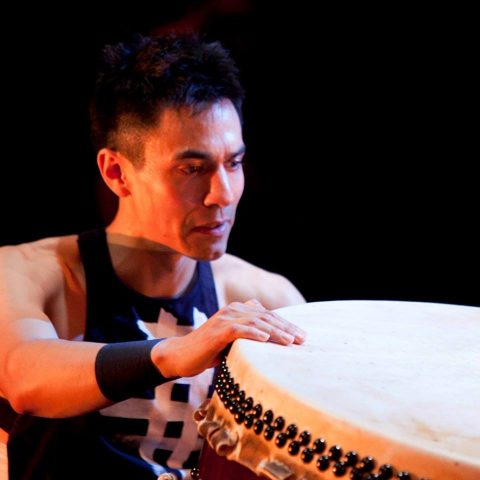

ISAKU KAGEYAMA. PHOTO BY KOJI SASAHARA.

ISAKU KAGEYAMA. PHOTO BY KOJI SASAHARA.

ISAKU KAGEYAMA is a taiko drummer and percussionist, working with Asano Taiko UnitOne in Los Angeles, film-scoring extravaganza “The Masterpiece Experience” and Tokyo ensemble Amanojaku. A magna cum laude Berklee College of Music graduate, he teaches at Wellesley, University of Connecticut and Brown. http://isakukageyama.com/

KOUZAN KIKUCHI. PHOTO BY JUNJI KUROKAWA.

KOUZAN KIKUCHI, shakuhachi player from Fukushima, studied minyo shamisen with his mother. A graduate of the Tokyo University of the Arts, he studied with National Treasure Houzan Yamamoto. He has worked with Ebizo Ichikawa, Shinobu Terajima and Motoko Ishii. In 2011, he became Tozanryu Shakuhachi Foundation “shihan” with highest honors.

JOE SMALL is a taiko artist, who is a member of Eitetsu Hayashi’s Fu-un no Kai and creator of the original concert, “Spall Fragments.” A Swarthmore graduate, he apprenticed for two years with Kodo, researched Japanese music as a Fulbright Fellow and holds an MFA in Dance from UCLA. He teaches at the Los Angeles Taiko Institute. www.joesmalltaiko.com

THE LIGHTING DESIGNER

BLU lived in New York for 20 years and was resident designer at the Cubiculo and La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club. A Bessie Award winner, he was lighting designer for renowned dance theater artists such as Sally Gross, Eiko and Koma, Ping Chong, Donald Byrd, Nancy Meehan and Paula Josa Jones.

THE FILMMAKER

YOSHIAKI TAGO

YOSHIAKI TAGO directed “A.F.O.,” “Believer,” “Worst Contact,” “Meido in Akihabara.” His short “The Song of a Tube Manufacturer” won the runner-up prize at the Yasujiro Ozu Memorial Film Festival in 2013. He serves as film adviser for Takashi Murakami. He has worked with Nobuhiko Obayashi, Takashi Miike and Macoto Tezuka. He is documenting “News from Fukushima” as a film.

Yuri Kageyama reports with a photographer in the Fukushima no-go zone. Photo by Kazuhiro Onuki.

What people are saying about NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA: MEDITATION ON AN UNDER-REPORTED CATASTROPHE BY A POET.

Yuri Kageyama, with her epic poem, has earned a place among the leading world poets. This work proves that the poet as a journalist can expose conditions that are ignored by the media. _ Ishmael Reed poet, essayist, playwright, publisher, lyricist, author of MUMBO JUMBO, THE LAST DAYS OF LOUISIANA RED and THE COMPLETE MUHAMMAD ALI, MacArthur Fellowship, professor at the University of California Berkeley, San Francisco Jazz Poet Laureate (2012-2016).

NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA is a commentary on what it means to be human in the 21st Century. While we are divided by race, ethnicity, language, geography and culture, the essence of our humanity remains constant. In NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA, the cast, director and playwright all come together to create a montage of courage, uncertainty and hope in the face of disaster. _ Basir Mchawi producer, community organizer and radio show host at WBAI Radio in New York, who has taught at the City University of New York, public schools and independent Black schools.

A truly emotional experience. _ Liliana Perez child psychologist and Ph.D.

A vital story of our times. Spoken word and music from a talented multicultural ensemble. A beacon of light in a darkening world. _ Paul Armstrong artistic director at International Arts Initiatives, a Vancouver-based nonprofit for cultural advancement through the arts and education.

I welcomed NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA _ into my consciousness, with deep gratitude, seeing it twice, two days in succession _ all the while marveling at the tough yet faithful production and its dedication to truth-telling. _ David Henderson poet, co-founder of Umbra and the Black Arts Movement, author of ‘SCUSE ME WHILE I KISS THE SKY. JIMI HEDNRIX: VOODOO CHILD.

Tragically, Fukushima is still constantly being shaken by earthquakes. NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA echoes the mourning of Bon Odori dance to warn us again and again that the nuclear age of post-World War II Japan has never ended. _ Hisami Kuroiwa movie producer and executive for “The Shell Collector,” “”Lafcadio Hearn: His Journey to Ithaca,” “Sunday,” “Bent” and the Silver Bear-winning “Smoke.”

Fukushima: Excellent musical accompaniment to poignant poetry, with minimal yet imaginative staging and choreography. Musicians were absolutely superb! _ Nana pianist and New Yorker.

What a delight was the new theater piece featuring Shigeko Suga, which did a short run at La MaMa. Ms. Suga and her fellow performers glided beautifully with wit, authority and grace through the stylized performances. See this show and be transported magically. _ George Ferencz co-founder of the Impossible Ragtime Theater, resident director at La MaMa (1982-2008), who has also directed at the Actors’ Theater of Louisville, Berkeley Rep and Cleveland Playhouse.

News that enraptures and engages through Sound. A Poet sings of the unreported calamity at Fukushima in NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA to Melvin Gibbs’ bass. _ Katsumi a Japanese living in New York.

It spoke of what’s most critically needed in this age. Despite advances in civilization and culture, the power of emotions has weakened, and people don’t know how to talk to each other. Everyone who took part in this performance, and those who came to see it, although of different races and thinking, all felt clearly the existence of what we know is so important, what we feel is so needed: Love. Love is not an abstract concept. It is about how we treasure our family, how we treat our lovers, our friends. I have lived to see many people who hurt others out of selfishness, betrayed others without qualms, and then went on to hide what they had done. But in the end, what is desired is not achieved, leaving only hunger, and, because of that, the cycle gets repeated again. What I saw here is not just cultural collaboration but what is at the center of that _ a warm feeling, and the expression of the message that the world cannot go on this way. I pray more people will be able to feel love through seeing this performance. I pray as someone who believes in love. _ Toshinori “Toshichael Jackson” Tani dancer, member of TL Brothers and instructor.

An excerpt from NEWS FROM FUKUSHIMA: “Hiroshima.” Filmed and edited by Yuri Kageyama.

Monisha Shiva. Photo by Tennessee Reed.