MY AP STORIES 2023

My AP Author Page where you can see all my stories, photos and video in one place.

My AP Stories for 2022 with links on the site to some earlier years. And My AP Stories for 2023:

My AP Story Dec. 14, 2023 on the Olympic bribery trial, in which the main defendant Haruyuki Takahashi asserts his innocence.

My AP Story Dec. 8, 2023 on Nintendo canceling and postponing events over threats.

My AP Story Dec. 5, 2023 on the ongoing Tokyo Olympic scandal trial.

My AP Story Nov. 18, 2023, an obit on religious leader Daisaku Ikeda.

My AP Story Nov. 8, 2023 on Nintendo working on a Zelda live-action film.

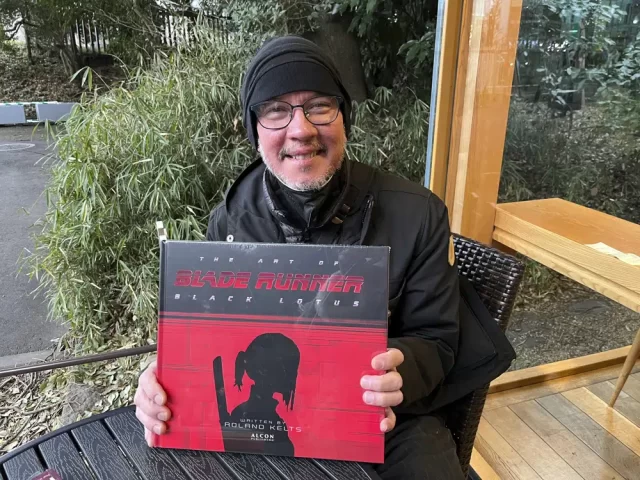

My AP Story Nov. 3, 2023 with my photo and video when I interview the director of the new Godzilla film.

My AP Story Nov. 29, 2023 on Toyota selling part of its stake in Denso.

My AP Story Nov. 1, 2023 on Toyota’s earnings getting a big boost from the cheap yen.

My AP Story Oct. 29, 2013 on the G-7 trade meeting.

My AP Story Oct. 25, 2023 on the Tokyo Mobility Show.

My AP Story Oct. 10, 2023 on the latest in the ongoing Tokyo Olympics bribery trial.

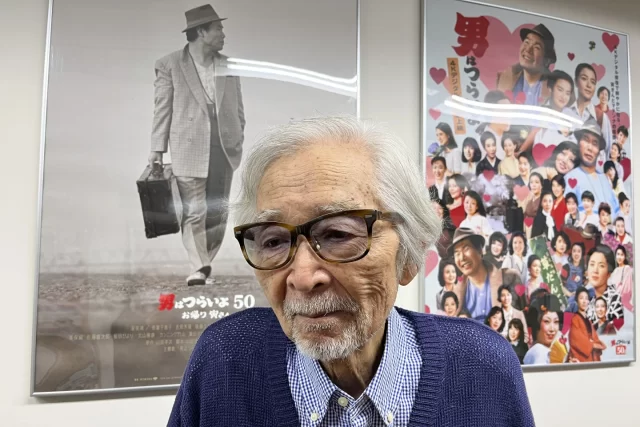

My AP Story and My AP Photos Oct. 7, 2023 when I interview director Yoji Yamada.

The story gets highlighted in Kabuki by Shochiku Oct. 14, 2023.

My AP Story Oct. 12, 2023 on Toyota’s move on EV batteries.

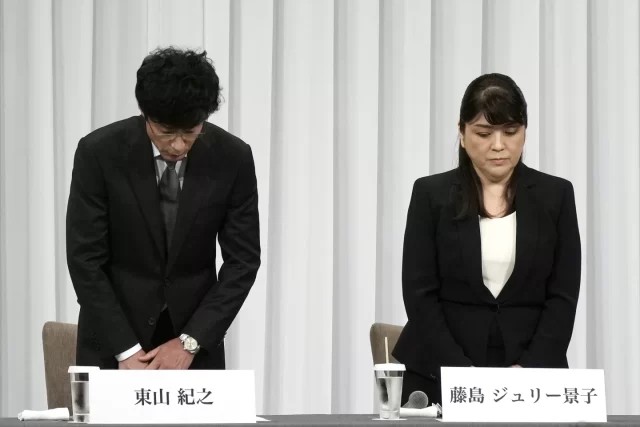

My AP Story Oct. 2, 2023 on the ongoing Johnny’s story whose name is now Smile-Up.

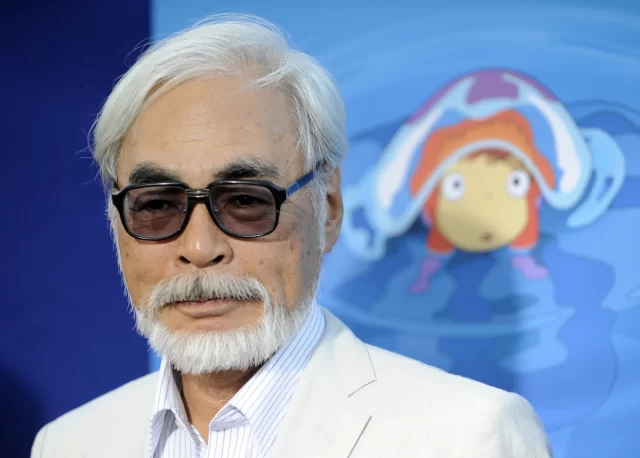

My AP Story Sept. 21, 2023 on Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli becoming Nippon TV’s subsidiary.

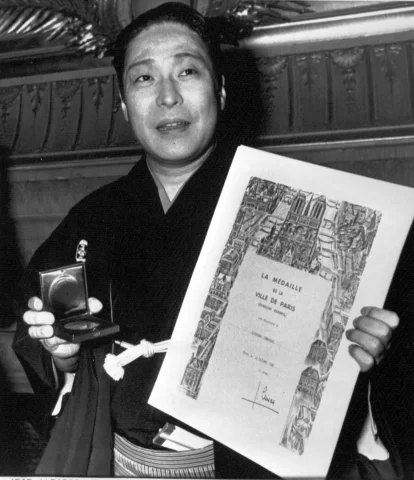

My AP Story Sept. 16, 2023, an obit on Kabuki actor and innovator Eno Ichikawa.

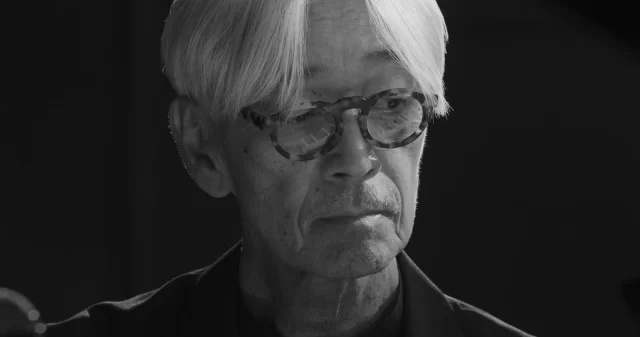

My AP Story Aug. 29, 2023 about Ryuichi Sakamoto’s final film.

My AP Story Sept. 2, 2023 with My AP Photos on Vocaloid star Hatsune Miku, 16 from 16 years ago.

My AP Story and My AP Photos Aug. 23, 2023 on digital clones in Japan.

My AP Story Oct. 6, 2023 in which I interview the CEO of major Tokyo developer Mori, and My AP Photos.

My AP Story Sept. 21, 2023 with the tender offer completed.

My AP Story Aug. 7, 2023 about Toshiba announcing a buyout offer.

My AP co-byline Story Sept. 15, 2023 on Arm’s IPO.

My AP Story Sept. 13, 2023 with the company setting up the compensation panel, foregoing pay.

My AP Story Sept. 7, 2023 on Johnny’s apologizing and promising compensation.

My AP Story July 13, 2023 about people coming forward alleging sexual abuse at Johnny’s.

My AP Story Sept. 4, 2023 about how the men who have come forward are hopeful, and fearful, ahead of the company’s first news conference on the scandal.

My AP Story Aug. 29, 2023 about a team looking into sexual assault allegations at Johnny’s and demanding Julie resign.

My AP Story Sept. 12, 2023 about companies dropping Johnny’s stars from ads.

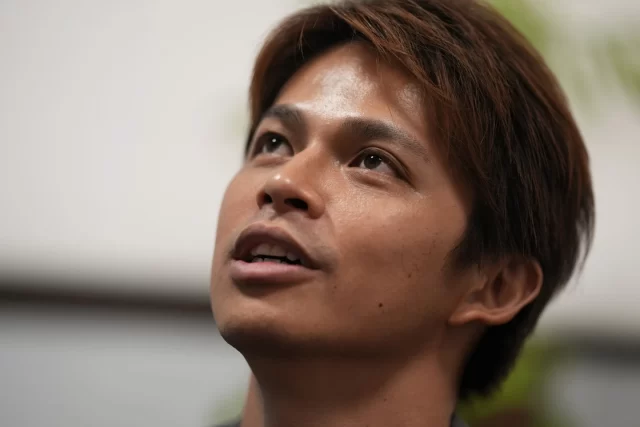

My AP Story and My AP Photos Aug. 4, 2023 about a U.N. group looking into the allegations at Johnny’s and how seven men saw that as a big step forward.

My AP Story and My AP Photo Aug. 14, 2023 on the men who came forward on the abuse speaking to the special team set up by Johnny & Associates.

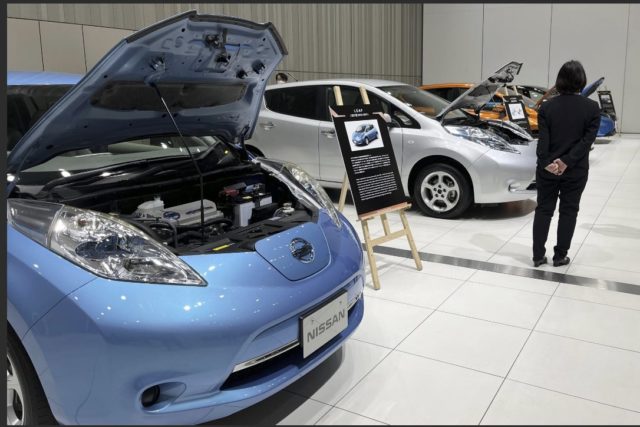

My AP Story and My AP Photo Aug. 31, 2023 on Nissan Leaf batteries being reused for a portable power station.

My AP Story Aug. 31, 2023 on a retail chain being sold to a U.S. fund.

My AP Story Aug. 15, 2023 on Japan’s economic growth surging on strong exports and tourism.

My AP Weather Story Aug. 6, 2023.

My AP Story June 29, 2023 on Fender’s first flagship store opening in Tokyo, and My AP Photo below.

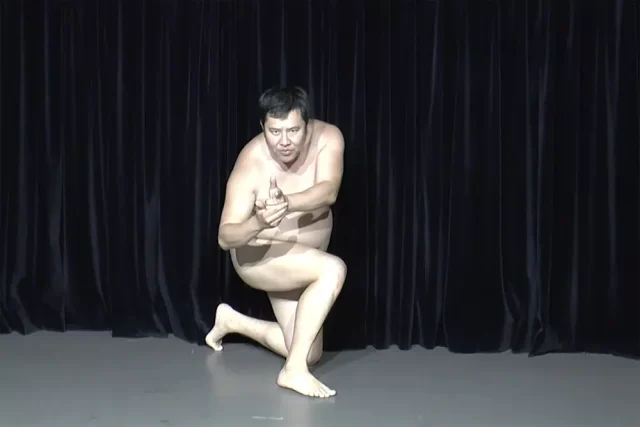

My AP Story May 29, 2023 about the comic who poses naked but, don’t worry, is wearing … pants.

My AP Video and My AP Photos that go with My AP Story. Thanks to Tony for sharing his Story.

My AP Story Aug. 9, 2023 on Sony’s financial results hit by a strike in the U.S. movie sector.

My AP Story Aug. 8, 2023 on SoftBank Group’s earnings report.

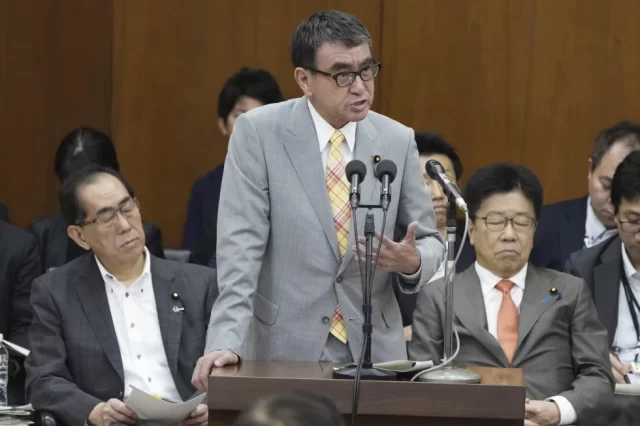

My AP Story July 6, 2023 on MyNumber in Japan.

My AP Story June 12, 2023 about Johnny’s in-house investigation on sexual abuse.

My AP Story June 19, 2023 on how wages and prices are rising.

My AP Story June 14, 2023 about how Toyota shareholders rejected a proposal on climate change.

My AP Story June 13, 2013 on Toyota’s EV initiatives.

My AP Story, My AP Photos and My AP Video June 2, 2023 about Maholo, who is French and Japanese _ and a Kabuki star.

My AP Story June 1, 2023 about Toyota’s liquid hydrogen racing car.

And My AP Photos when I get close to Akio Toyoda aka Morizo, who drove the hydrogen racing car.

My AP Story May 27, 2023 about Le Mans to include hydrogen vehicles.

My AP Story May 30, 2023 about Toyota, Daimler Truck, Hino, Mitsubishi Fuso joining forces in ecological technology.

My AP Story May 20, 2023 about Toyota disclosing improper crash tests.

My AP Story May 18, 2023 about Japan’s prime minister meeting with chip makers.

My AP Story May 15, 2023 about the apology from the talent agency mired in a sex scandal.

My AP Story May 17, 2023 on Japan economic growth.

My AP Story May 11, 2023 on Nissan’s earnings.

My AP Story May 11, 2023 on SoftBank’s earnings.

My AP Story May 11, 2023 on Honda’s earnings.

My AP Story May 12, 2023 on a data breach on 2 million Toyota vehicles.

My AP Story May 10, 2023 on Toyota’s earnings results.

My AP Story May 2, 2023 on BYD EVs starting to crack the Japan market and My AP Photos.

My AP Story May 1, 2023 about Jack Ma being a professor at a Japanese university.

My AP Story April 26, 2023 on Honda outlining its EV strategy.

My AP Story April 21, 2023 with My AP Photo, in which Toyota’s new president vows to push ahead with EVs.

My AP Story April 21, 2023 on a verdict in the Olympic bribery trial.

My AP Story April 15, 2023 on Takeshi Kitano’s latest film headed to Cannes.

My AP Story April 14, 2023 in which I interview Makoto Shinkai about his filmmaking.

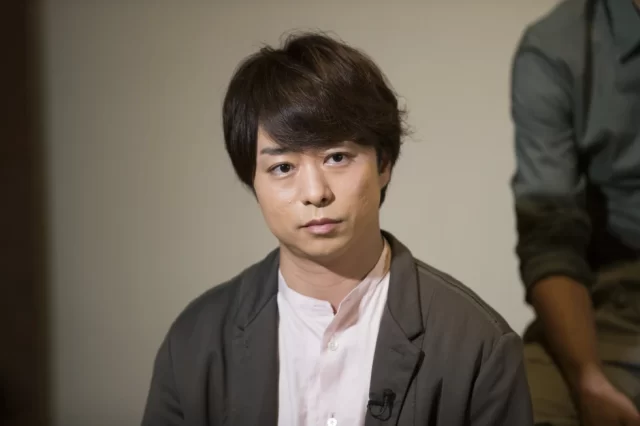

My AP Story April 12, 2023 on a former Johnny’s Junior alleging sexual abuse.

My AP Story April 11, 2023 on climate change in Japan.

My AP Story April 3, 2023, an Obit on Ryuichi Sakamoto.

My AP Story April 6, 2023 about the Olympic scandal and the Sapporo election.

My AP Story March 24, 2023 on Toshiba’s tender offer.

My AP Story March 19, 2023 on how the hit WBC pepper-grinder move is out in high school baseball.

My AP Story March 8, 2023 on how women prosecutors are fighting crime, gender inequality.

My AP Story March 6, 2023 and My AP Photo (below) on One Piece going Hollywood.

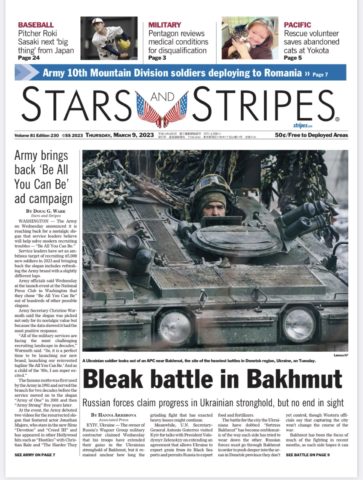

My AP Story March 7, 2023 on Roki Sasaki at the World Baseball Classic, which makes it into the Stars and Stripes.

My AP Story March 17, 2023 on business leaders from South Korea and Japan agreeing to work together.

I’m a Contributor to this AP Story March 19, 2023 on a North Korean missile launch.

My AP Story March 14, 2023 on Trevor Bauer signing with a Yokohama club.

My AP Story Feb. 26, 2023 on a young Ukrainian making Japan his new home.

My AP Story and My AP Photos March 9, 2023 on Nissan’s electrification move.

My AP Story Feb. 28, 2023 about Dentsu and others getting charged in the Olympic bid-ridding scandal.

My AP Story March 9, 2023 about Japan’s economic growth staying flat.

My AP Story March 10, 2023 on the next central bank governor.

My AP Story Feb. 14, 2023 on a scholar being nominated to head Japan’s central bank.

My AP Story Feb. 27, 2023 about Nissan accelerating its shift toward electric vehicles.

I’m a Contributor to this AP Story Feb. 18, 2023 about North Korea firing yet another missile.

My AP Story Feb. 17, 2023 on an Olympic bribery scandal trial opening in Tokyo.

My AP Story Feb. 14, 2023, an Obit on Shoichiro Toyoda, the son of Toyota’s founder.

My AP Story Feb. 13, 2023 on Toyota’s new leadership team.

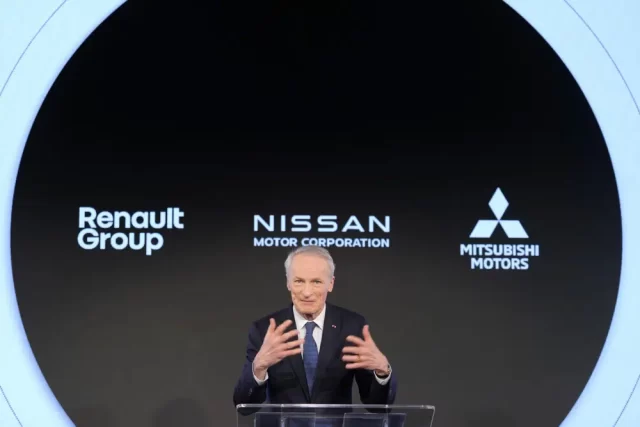

My AP Story Feb. 6, 2023 with Kelvin Chan in London about Nissan and Renault balancing their mutual shareholdings.

My AP Story Feb. 4, 2023 on the prime minister’s aide being forced to leave over discriminatory remarks.

My AP Story Feb. 8, 2023 on arrests, now in a bid-rigging investigation into the Olympics.

My AP Story Feb. 2, 2023 on Kadokawa promising better governance in the Olympic scandal.

My AP Story Feb. 2, 2023 on Honda’s hydrogen plans.

My AP Story Feb. 2, 2023 on Sony’s new managerial leadership.

My AP Story Jan. 30, 2023 on Nissan, Renault balancing out the shares they hold in each other.

My AP Story Jan. 20, 2023 on Japan’s inflation.

My bit on the Japanese minister is part of this AP Story Jan. 18, 2023 on the Davos World Economic Forum.

My AP Story Jan. 13, 2023 on Akio Toyoda talking about converting old cars into ecological ones.

My AP Story Jan. 26, 2023 on Toyoda stepping aside as CEO.

I’m a Contributor to this AP Story Jan. 6, 2023 on Samurai Japan at the World Baseball Classic.

I’m also a Contributor to this AP Story Jan. 10, 2023 about a Rangers pitcher signing with SoftBank.

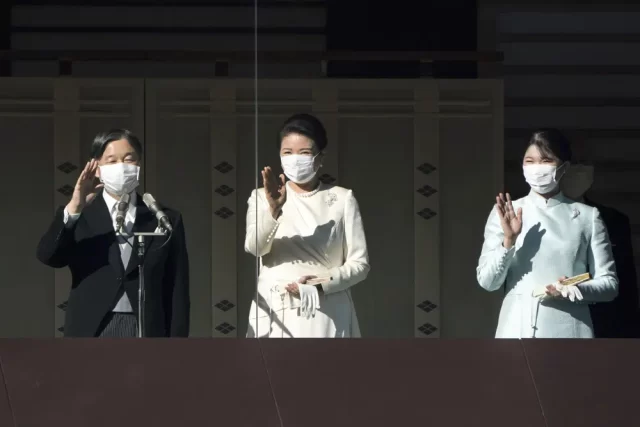

My AP Story Jan. 2. 2023 on the Emperor greetings well-wishers.