I met the former inmate behind this story a few years ago, in 2016, when I was putting together my story “The Very Special Day” with artwork by Munenori Tamagawa. I was thinking of just stapling together printouts, but the visual artist had other ideas. He wanted a real book, and he said he knew someone who knew how to design books, a skill, as it turned out, he had learned in a Japanese prison. I didn’t ask questions. I just assumed he had committed a serious crime because of the long time he had been incarcerated, but felt he deserved to be treated no different from anyone else as he had served his time. I did not even know until he told me his story that he was asserting his innocence. This is his story:

He spent 15 years behind bars for a murder he confessed to, but he says he didn’t commit. His father hanged himself in shame. While in prison, he bit off a piece of his arm in a suicide attempt. Placed on half a dozen tranquilizer pills, he was an addict by the time he finally got out, four years ago.

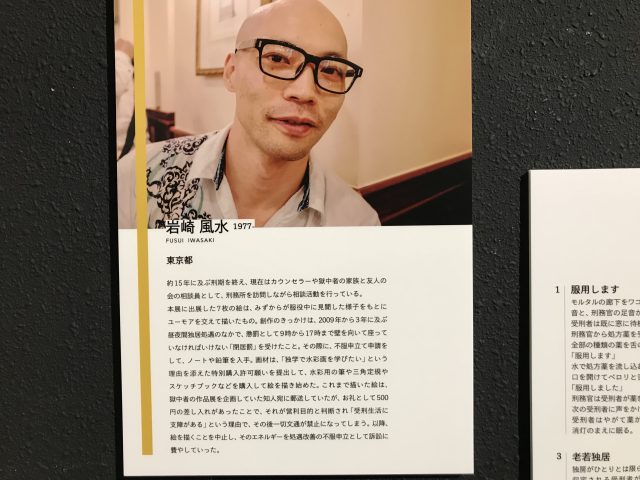

Fengshui Iwazaki, who has changed his name to protect himself from the social backlash, is still trying to adjust to being back in the real world.

“Fifteen years _ that’s a whole generation in a lifetime,” he says, his eyes clear, child-like, much younger than his 41 years.

His story underlines the treatment convicts get in Japan, a society that’s so insular and crime-free most people don’t know much about what it’s like to live the life of a criminal. The arrest of Nissan’s former Chairman Carlos Ghosn, charged with financial misconduct, is helping bring international scrutiny to this legal system, which human rights groups have long criticized as harsh and unfair.

Iwazaki had never before spoken to me about his experiences, how two decades ago, he had made headlines as a murderer.

“It was as though I was a monster,” Iwazaki recalled.

^____<

Iwazaki and others who went through Japan’s criminal system say prosecutors and police come up with a story-line for a confession. While interrogated, Iwazaki was taken to the mountains where the body had been found and directed to point in the right spots, he said.

His girlfriend had been strangled to death, and he instantly emerged the prime suspect.

He resisted at first but signed the confession after three weeks of being interrogated daily without a lawyer present, standard practice in Japan.

He says he was bullied, his hair pulled, the table banged. After a while, it was easy to cave in.

He believes the real murderer might be the man who had adopted his then-3-year-old daughter from a previous relationship. He had planned to live near her someday, not ever telling her he was the father, just to be close to her. She died in a car accident while he was serving time.

Prosecutors say they are merely doing their jobs and didn’t create the system.

Defense lawyers say suspects sign false confessions and don’t realize it’s too late to assert innocence later in a trial.

That’s why it is called “hostage justice.”

Judges tend to believe the prosecutors’ story line: the conviction rate in Japan is higher than 99%.

Going against such a powerful trend takes tremendous courage. Unlike the U.S., prosecutors can appeal, meaning innocent verdicts can get overturned in a higher court.

^___<

The life of imprisonment Iwazaki describes is austere, isolated and regulated. Each prisoner gets a tiny cell with a toilet and bedding, unless the prison gets crowded and cells get shared, a condition that’s increasingly rare.

Communication among inmates is limited to the 30 minutes of outdoor exercise, or the evening hours, during which TV is allowed.

Whenever inmates are transported, they wait in enclosed booths lined next to each other so prisoners won’t mingle, called “bikkuri-bako,” or “jack-in-the-box.”

Every morning, the convict changes into green prison garb and gets marched to a factory within the prison grounds.

Iwazaki did menial work like placing wooden chopsticks into paper wrapping and packing them in boxes. He also learned how to work the printing presses.

The toughest time was his three-year solitary confinement doled out as punishment for being a troublemaker, he said.

One time, out of frustration, he smashed a window with his bare hand, which added half a year to his sentence.

He was always curious about why others were locked up.

One inmate, he learned, had tried to steal money from an ATM to send his son to college. When a guard found him, he used a stun gun. The guard had a weak heart and died. And so the charge became murder while committing grand larceny, a serious offense.

“There are no really bad people in prison,” Iwazaki says with a conviction that is startling.

^____<

There is little in Japanese society that helps people adjust to life after incarceration.

When Iwazaki was released, he only had 1,000 yen ($9). He checked into a hospital, pleading insanity. He was running out of the pills prescribed at the prison.

He finally made it to Eizo Yamagiwa, a filmmaker who has devoted his life to supporting prisoners. Yamagiwa, who had visited Iwazaki in prison, gave him money, and Iwazaki finally made it home to his mom.

Yamagiwa says only the authorities’ side of the story gets relayed in Japan, influencing judges and juries so that trials tend to merely work as rubber-stamps for the prosecutors.

The prison system, he said, is so devastating most people come out sick and unable to continue with their lives.

He said Iwazaki was an exception in working hard to live a normal life.

^___<

Iwazaki, who had originally planned to become a schoolteacher, has had his life forever changed.

Retrials to try to overturn guilty verdicts are rarely granted in Japan. Usually, totally new evidence such as a DNA test is needed.

Iwazaki is hesitant even to try. His case is tough because of the mounds of evidence submitted during his trial, including his confession. His mother has asked he doesn’t pursue a retrial; she doesn’t want to think about any of it ever again.

Iwazaki lives alone in a stark room with a tiny drab kitchen and a bathroom. A desk and two chairs are the only furniture.

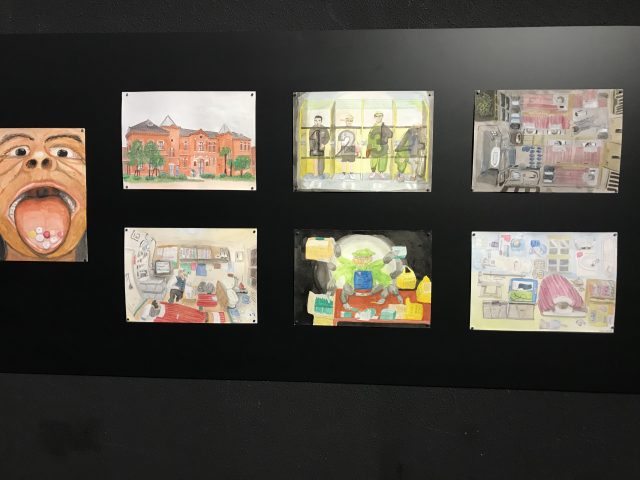

On the walls are two drawings signed Masahiro, a man who died on death row. Done meticulously and entirely by pen and pencils, one depicts a bouquet of red roses, the other, Mary and baby Jesus. No one except for Iwazaki had claimed them.

Iwazaki also drew pictures while in prison: A big close-up of his open mouth filled with pills, a bird’s eye view of his cell, an inmate working so hard in the factory he is turning into a blur.

The drawings were part of a show of “art by outsiders” in April 2019, in Tokyo, a milestone for Iwazaki. While in prison, authorities had forbidden such exhibits.

Iwazaki is also in a training program to counsel addicts. He already works as a counselor, having studied various therapy methods, which he says helps calm him. Completing the training means better pay.

He has also found a girlfriend, a carefree woman who works at a dot.com and is passionate about saving lions in Africa. They plan to get married and maybe have children.